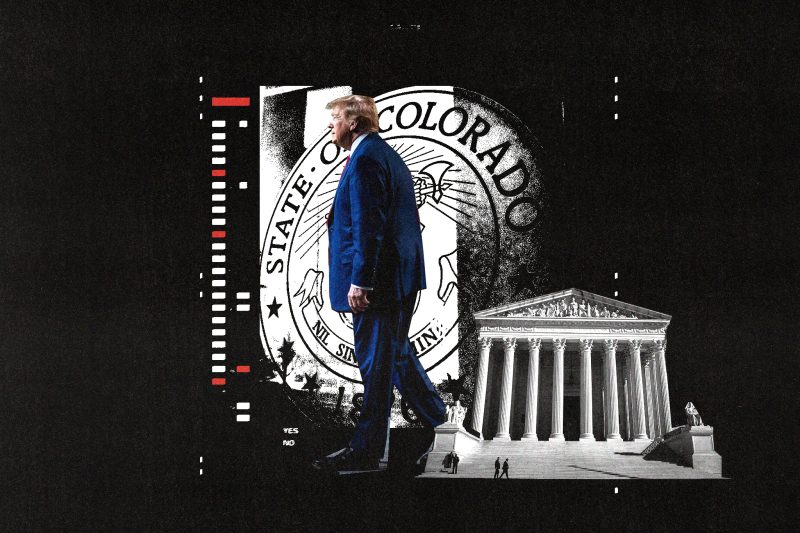

In Trump’s Colorado case, Supreme Court will make and face history

The Supreme Court on Thursday will confront the critical question of Donald Trump’s eligibility to return to the White House, hearing argument in an unprecedented case that gives the justices a central role in charting the course of a presidential election for the first time in nearly a quarter-century.

The justices will decide whether Colorado’s top court was correct to apply a post-Civil War provision of the Constitution to order Trump off the ballot after concluding his actions around the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol amounted to insurrection. Primary voting is already underway in some states. Colorado’s ballots for the March 5 primary were printed last week and include Trump’s name. But his status as a candidate will depend on what the Supreme Court decides.

Unlike Bush v. Gore in 2000, when the court’s decision handed the election to George W. Bush, the case challenging Trump’s qualifications for a second term comes at a time when a large swath of the country views the Supreme Court through a partisan lens and a significant percentage still believes false claims that the last presidential election was rigged.

The justices — especially their cautious, consensus building chief, John G. Roberts Jr. — may be reluctant to wade into such a politically fraught dispute, experts say. The court could rule more narrowly, finding, for example, that Colorado was wrong to bar Trump from the ballot because of a technicality.

But election law experts have implored the justices to definitively decide the key question of whether Trump is disqualified under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, settling the issue nationwide so that other states with similar challenges to Trump’s candidacy follow along.

They warn of political instability not seen since the Civil War if the court was to overturn Colorado’s ruling but leave open the possibility that Congress could try to disqualify Trump later in the process, including after the general election.

“You can see this one coming. There are flashing red lights warning 10 months before the election that chaos this time is not only possible but more than likely given that 2020 broke the norm and dented the guardrails,” said veteran Republican election lawyer Benjamin Ginsberg, who played a central role for Bush in the Florida recount.

Trump’s eligibility is not the only question before the court that could affect the former president’s political future. Later this term, the justices are set to review the validity of a law that was used to charge hundreds of people in connection with the Jan. 6 riot and is also a key element of Trump’s four-count federal election obstruction case in Washington. Trump’s claim that he is protected by presidential immunity from being prosecuted for trying to block Joe Biden’s 2020 election victory also appears headed to the high court after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled against Trump this week.

In the Colorado case, the justices will have to weigh untested legal issues against the backdrop of broad concerns about democracy. Put simply, should the ramifications of disqualifying the leading Republican candidate in the midst of the primary election outweigh the consequences of allowing a candidate to run again after he tried to subvert the outcome of the last election?

Justice Clarence Thomas is the only sitting justice who was on the bench in December 2000 when the high court put a stop to the Florida recount and sealed Bush’s victory. Democratic lawmakers have asked him to recuse from the Colorado case because of his wife’s involvement in trying to overturn the 2020 election results, but he is not expected to do so. Three other justices, including Roberts, were young lawyers helping the Bush campaign in Florida, personally witnessing the stakes of having the nation’s highest court decide the outcome of a national contest.

The challenge to Trump’s eligibility in Colorado was brought by six voters — four Republicans and two independents. They convinced the Colorado Supreme Court that Trump engaged in insurrection when he summoned his supporters to Washington and encouraged the angry crowd to try to prevent Congress from certifying Biden’s 2020 election. Maine’s secretary of state reached the same conclusion, and both states put their decisions on hold while litigation continues.

Once Trump appealed the Colorado decision, the justices quickly scheduled argument for Feb. 8. The court could rule at any time after that. In Bush v. Gore, with the voting done and the outcome hanging in the balance, the justices acted with extraordinary speed, issuing an opinion one day after the argument.

“It’s a precarious place to be, but the court has decided literally dozens of election cases since 2000. The stakes are just much higher,” said Richard L. Hasen, an election law expert who teaches at UCLA’s law school.

“I’m skeptical that this case is actually going to be decided on the historical record regardless of what the court says,” he added. The political implications of the ruling, “more than anything else, are going to be weighing on the justices — consciously or subconsciously.”

Historians, academics, former government officials and members of Congress have submitted dozens of filings laying out possible paths the Supreme Court could take to resolve whether the constitution disqualifies Trump from a second term.

The court’s conservative majority favors originalism and textualism — methods of interpretation that direct judges to interpret the words of the Constitution as they were understood at the time they were written and to consider the words of laws under review. Conflicting interpretations of the text and history of Section 3, also known as the disqualification clause, are likely to dominate Thursday’s argument.

The disqualification clause was initially intended to guard against former Confederates returning to positions of power after the Civil War. It says no person who previously took an oath “as an officer of the United States” to “support the Constitution” and then violated that oath by engaging in insurrection or rebellion can “hold any office, civil or military, under the United States.” The text does not specify who is supposed to enforce the clause or when it should be invoked, leading some experts to say Congress could try to prevent Trump from being sworn in if he is elected.

Trump’s lead lawyer, Jonathan Mitchell, told the court Section 3 does not apply to Trump for several reasons. Among them: The president is not an “officer of the United States,” which is the term the section uses to discuss potential insurrectionists; Congress, not state courts or state officials, enforces the disqualification provision; and Trump did not engage in insurrection.

“President Trump never told his supporters to enter the Capitol, and he did not lead, direct, or encourage any of the unlawful acts that occurred at the Capitol,” Mitchell wrote in his filing. He added: “Giving a passionate political speech and telling supporters to metaphorically ‘fight like hell’ for their beliefs is not insurrection either.”

Trump distinguishes between executive branch “officers” appointed by the president and referred to in other sections of the Constitution, and a president who is elected. Separately, Trump’s lawyers say the president takes an oath to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution” — distinct from the oath other officials take to “support the Constitution.”

Conservative legal scholars and former Republican attorneys general Edwin Meese III, Michael B. Mukasey and William P. Barr also told the justices that the Colorado court got it wrong. Disqualifying Trump, they wrote, would have “ruinous consequences for our democratic republic.”

They urged the justices to “resist any interpretation of Section 3 that empowers partisan public officials to unilaterally disqualify politicians from the opposing party — and especially in this case, the current leader of the opposition party.” They also suggested a Republican secretary of state could disqualify Biden from the ballot, charging that his policies constitute an “insurrection.” Four voters in Illinois unsuccessfully pursued such a challenge recently, based on Biden’s actions at the U.S.-Mexico border.

But other conservative legal scholars and leading historians say the original meaning of the disqualification clause is clear. Section 3 must be read “sensibly, naturally and in context, without artifice or ingenious invention,” University of St. Thomas law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen and University of Chicago law professor William Baude, a former law clerk to Roberts, said in a law review article.

“A reading that renders the document a ‘secret code’ loaded with hidden meanings discernible only by a select priesthood of illuminati is generally an unlikely one,” they wrote.

Historians and the Colorado voters working with Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington also cast doubt on the idea that the framers of Section 3 would have created a loophole for oath-breaking, insurrectionist former presidents. In the aftermath of the Civil War, the framers were concerned about Confederate sympathizers ascending to high government posts, including a possible bid for the presidency by Jefferson Davis, a member of Congress from Mississippi who served as the first and only president of the Confederacy.

A group of experts in democracies around the world acknowledged to the court the grave consequences of removing a presidential candidate from the ballot. But they warned that failing to act, if action is justified, could have equally dire consequences.

“Taking a popular candidate out of consideration can breed distrust in the system. And yet, this concern is equally valid if the court fails to act: distrust in the system is precisely what has been fueled by the insurrection and claims of fraud perpetuated by the former President,” said the brief those experts submitted in support of the Colorado voters.

State officials have traditionally had broad power to set the rules for elections and often keep people off the ballot who do not meet age or citizenship qualifications. Several briefs in favor of enforcing Section 3 quote from a 2012 ruling by then-appeals court judge Neil M. Gorsuch that is likely to surface during argument. The brief order from Gorsuch, now a justice and part of the Supreme Court’s conservative majority, affirmed Colorado’s authority to keep off the ballot a presidential candidate who was not a natural-born citizen.

A “state’s legitimate interest in protecting the integrity and practical functioning of the political process permits it to exclude from the ballot candidates who are constitutionally prohibited from assuming office,” Gorsuch wrote.

Even so, election law experts said the odds are in Trump’s favor, because the former president only needs to win on one of the issues before the court — whether he participated in insurrection, for example, or whether Section 3 applies to presidents — to get his name back on the ballot.

Whatever the court decides is likely to polarize voters just as the court’s decision in Bush v. Gore split the country 24 years ago.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett was just three years out of law school when she was sent to Florida to help Bush’s legal team in a dispute over the tallying of absentee ballots. Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, then in private practice, helped oversee a recount in central Florida as part of the Bush campaign. And Roberts, who as partner in a Washington law firm had already argued dozens of cases before the high court, was sent to Tallahassee to advise the Bush campaign and help prepare the lawyer appearing before the Florida Supreme Court.

The litigation surrounding the 2000 election was intense, fast-moving and high stakes. Even though the high court endured sharp criticism for intervening in the election in favor of Bush, Vice President Al Gore accepted the decision and public approval rebounded.

The country is far more divided now, with many skeptical of the court and the integrity of elections. On the campaign trail, Trump continues to falsely refer to the 2020 election as stolen. He has refused to commit to accepting the results of the 2024 election if he is not the winner.

Public opinion of the court has also declined to near record lows, according to Gallup, a dip tied to the court’s elimination of the nationwide right to abortion. Less than half of Americans say they have a great deal or moderate trust in the court to make the “right decision” in cases related to the 2024 election, according to a new CNN poll.

Those involved in Bush v. Gore said even in this era, public acceptance of the court’s ruling will be greater and acceptance by members of Congress higher if the court can reach a near-unanimous decision. Theodore B. Olson, a former solicitor general who argued on Bush’s behalf, said the American people also will be more likely to accept the court’s decision if it is resolved quickly and fully explained.

But reaching a decision that avoids the court’s 6-3 ideological split may be difficult.

Three of the sitting justices were nominated by Trump, cementing a conservative supermajority that has upheld many of the former president’s policies but has not ruled in his favor on matters involving access to his financial records and to White House documents sought by a congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack.

As chief justice, Roberts will be looking for common ground. He has previously raised concerns about judges being perceived as picking winners in election-related disputes. In a 2017 case involving partisan gerrymandering, Roberts highlighted the problem in a hypothetical during oral argument.

If, for instance, the Democrats win, Roberts said, the man on the street will ask, “Why?” and not be convinced of a complex formula used to assess the voting maps.

“The intelligent man on the street is going to say that’s a bunch of baloney. It must be because the Supreme Court preferred the Democrats over the Republicans,” Roberts said, adding, “And that is going to cause very serious harm to the status and integrity of the decisions of this Court in the eyes of the country.”

The case is Donald J. Trump v. Norma Anderson.

Scott Clement in Washington and Patrick Marley contributed to this report.